MODELO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

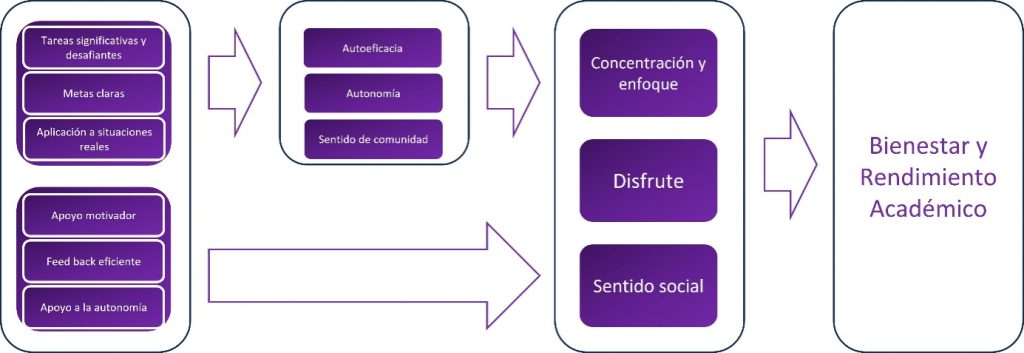

Premisa 3. Hacia un modelo de enseñanza-aprendizaje óptimo

Estado de flujo (engagement)

El compromiso del estudiante es un constructo, enraizado en la teoría de flujo (Csikszentmihalyi et al.,1993), que describe aspectos plásticos del comportamiento que son beneficiosos para el éxito de los procesos y calidad del aprendizaje (Corno y Mandinach, 1983; Schiefele, 2009). Es un constructo multifacético que incorpora aspectos que se refuerzan e interconectan mutuamente (Wang et al., 2016). Algunos revisores han sugerido que es útil distinguir formas afectivas, conductuales y cognitivas (Christenson et al., 2012; Fredricks et al., 2004, 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Otros estudios empíricos se han centrado en la validación de estos constructos, incluidas las dimensiones desvinculadas y su relación con otras facetas del compromiso (Hospel et al., 2016). Otros estudios de validación han encontrado diferencias más pronunciadas entre la faceta afectiva y las otras facetas del engagement (Ben-Eliyahu et al., 2018) y se han encontrado relaciones positivas entre el engagement afectivo y el engagement cognitivo-conductual de los estudiantes (Pöysä et al., 2018).

Además de multidimensional, la implicación (engagement) es dinámica, fluctuante, dependiente del contexto e interactiva (por ejemplo, Goldin, Epstein, Schorr y Warner, 2011). La investigación sobre el flujo y la calidad de la experiencia en entornos de aprendizaje ha buscado capturar y explicar los factores del ambiente aprendizaje que modelan la implicación del alumnado (Shernoff et al., 2016).

Arraigado en la teoría del flujo (Shernoff, Abdi, Anderson y Csikszentmihalyi, 2014), el compromiso de los estudiantes se puede conceptualizar como la experiencia intensificada y simultánea de concentración, interés y disfrute (Shernoff, 2013). Estos tres componentes no sólo son fundamentales para que las experiencias fluyan, sino que también se han relacionado con rendimiento académico (Corno y Mandinach, 1983; Schiefele, 2009; Csikszentmihalyi et al.,1993). De manera similar al flujo, lograr un estado ideal de compromiso, que incluya aspectos tanto laborales (es decir, concentración) como lúdicos (p. ej., disfrute), puede ser intrínsecamente significativo y también puede prevenir de la desconexión y sus consecuencias negativas para el aprendizaje (Shernoff, 2013).

La intensidad de la tarea, el compromiso cognitivo y el compromiso social se han utilizado para medir la capacidad de estimulación cognitiva de las tareas actuando como protección del deterioro cognitivo (Vujic et al., 2022). También, el compromiso cognitivo se ha utilizado como medio para reducir la variabilidad cognitiva dada su asociación con el deterioro cognitivo futuro (Brydges & Bielak, 2019). Otros hallazgos sugieren que el compromiso cognitivo mantenido a través de actividades novedosas y cognitivamente exigentes mejora la memoria en edades avanzadas (Park et al., 2014).

Referencias

Ben-Eliyahu, A., Moore, D., Dorph, R., & Schunn, C. D. (2018). Investigating the multidimensionality of engagement: Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement across science activities and contexts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 87-105.

Brydges, C. R., & Bielak, A. A. (2019). The impact of a sustained cognitive engagement intervention on cognitive variability: The synapse project. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 3(4), 365-375.

Christenson, S. L., & Reschly, A. L. (2012). Check & Connect: Enhancing school completion through student engagement. In Handbook of youth prevention science (pp. 327-348). Routledge.

Corno, L., & Mandinach, E. B. (1983). The role of cognitive engagement in classroom learning and motivation. Educational psychologist, 18(2), 88-108.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1993). Activity and happiness: Towards a science of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 1(1), 38-42.

Findsen, B., McCullough, S., & McEwan, B. (2014). Later life learning for adults in Scotland: Tracking the engagement with and impact of learning for working-class men and women. In Challenges and Inequalities in Lifelong Learning and Social Justice (pp. 97-118). Routledge.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of educational research, 74(1), 59-109.

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and instruction, 43, 1-4.

Goldin, G. A., Epstein, Y. M., Schorr, R. Y., & Warner, L. B. (2011). Beliefs and engagement structures: Behind the affective dimension of mathematical learning. ZDM, 43, 547-560.

Hospel, V., Galand, B., & Janosz, M. (2016). Multidimensionality of behavioural engagement: Empirical support and implications. International Journal of Educational Research, 77, 37-49.

Park, D. C., Lodi-Smith, J., Drew, L., Haber, S., Hebrank, A., Bischof, G. N., & Aamodt, W. (2014). The impact of sustained engagement on cognitive function in older adults: The Synapse Project. Psychological science, 25(1), 103-112.

Pöysä, S., Vasalampi, K., Muotka, J., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Nurmi, J. E. (2018). Variation in situation-specific engagement among lower secondary school students. Learning and Instruction, 53, 64-73.

Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. Handbook of motivation at school, 197-222.

Shernoff, D. J. (2013). Optimal Learning Environments to Promote Student Engagement. Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7089-2

Shernoff, D. J., Abdi, B., Anderson, B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow in schools revisited: Cultivating engaged learners and optimal learning environments. In Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 211-226). Routledge.

Shernoff, D. J., Kelly, S., Tonks, S. M., Anderson, B., Cavanagh, R. F., Sinha, S., & Abdi, B. (2016). Student engagement as a function of environmental complexity in high school classrooms. Learning and Instruction, 43, 52-60.

Vujic, A., Mowszowski, L., Meares, S., Duffy, S., Batchelor, J., & Naismith, S. L. (2022). Engagement in cognitively stimulating activities in individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: relationships with neuropsychological domains and hippocampal volume. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 29(6), 1000-1021.

Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43, 16-26.